Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes

| Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes | |

|---|---|

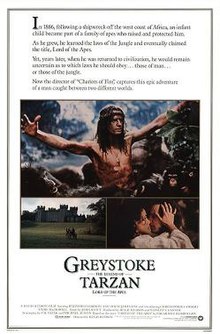

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Hugh Hudson |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs |

| Produced by | Hugh Hudson Stanley S. Canter |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Alcott |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

| Music by |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 130 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[2] or $27 million[3] |

| Box office | $45.9 million |

Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes is a 1984 adventure film directed by Hugh Hudson based on Edgar Rice Burroughs' novel Tarzan of the Apes (1912). Christopher Lambert stars as Tarzan (though the name Tarzan is never used in the film's dialogue) and Andie MacDowell as Jane; the cast also includes Ralph Richardson (in his final role), Ian Holm, James Fox, Cheryl Campbell, and Ian Charleson.[4]

Greystoke received three Oscar nominations at the 57th Academy Awards ceremony for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Richardson, Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, and Best Makeup. It became the first Tarzan feature film to be nominated for an Academy Award; the later Disney animated feature film adaptation became the first one to win an Oscar.

Plot

[edit]John, Lord Clayton, the heir to the 6th Earl of Greystoke, and his wife Alice are shipwrecked on the Congolese coast. John builds a home in the trees, and Alice gives birth to a son. She later grows ill from malaria and dies. While John is grieving her, the treehouse is visited by Mangani apes, one of whom kills him. Kala, a female ape carrying her dead infant, hears the cries of the human baby in his crib. She adopts the boy and raises him as a member of the clan as he grows up naked, wild, and free.

At age one, the boy learns how to walk. At age five, he knows how to swing on vines and is still trying to fit in with his ape family. When a black panther attacks, he learns how to swim to evade it while another ape is killed.

At age 12, the boy discovers the treehouse. He finds a wooden block, with pictures of a boy and a chimpanzee painted on it. Seeing himself in a mirror, the boy recognizes he is different from the rest of his ape family. He also discovers his father's hunting knife. The objects fascinate the boy, who takes them with him; but is ambushed by the ape Kerchak who savagely beats the boy before his ape mother and father arrive. The boy is nursed back to health and gets back at Kerchak by urinating on him, learning to outwit the stronger opponent rather than fight him directly. One day, his mother is killed by a native hunting party, and he kills one of them in revenge.

Years later, Belgian explorer Phillippe d'Arnot is traveling with a band of British adventurers along the river. He is disgusted by Major Jack Downing who hunts animals for sport. A band of natives attack the party, killing everyone except Phillippe, who, injured, hides in the trees. The young man in a loin cloth finds Phillippe and nurses him back to health. D'Arnot discovers that the man is a natural mimic and teaches him to speak rudimentary English. After deducing who this man's father and mother are, d'Arnot calls him "Jean". John agrees to return to England with him and reunite with his human family.

On arrival at Greystoke, the family's country estate in Scotland, John is welcomed by his grandfather, the 6th Earl of Greystoke, and his ward, a young American called Jane. The Earl still grieves the loss of his son and daughter-in-law but is very happy to have his grandson home. He displays eccentric behaviour and often seems to think his grandson is his son.

John is treated as a novelty by the locals, and some of his behavior is seen as threatening. He befriends a mentally disabled worker on the estate and in his company relaxes into his natural ape-like behaviour. Jane, meanwhile, teaches John more English, French, and social skills. They become very close and one evening make love in secret.

Lord Greystoke enjoys renewed vigour at the return of his grandson and, reminiscing about his childhood game of using a tray as a toboggan on a flight of stairs, decides to relive the old pastime. He crashes at the foot of the stairs and dies, apparently from a head injury. At his passing, John mourns as he did in Africa following the death of Kala.

John inherits the title Earl of Greystoke. Jane helps John through his grief, and they become engaged. He is also cheered up when Phillippe returns. One day, while visiting London's Natural History Museum with Jane, John is disturbed by the displays of stuffed animals. He discovers many live, caged apes from Africa, including his adoptive father, Silverbeard. John releases Silverbeard and other caged animals. Pursued by police and museum officials, they reach a park, where Silverbeard is fatally shot. John is devastated.

Righteously sickened by a society where humans mistreat their fellow animals as well as each other, while also tired of the other nobles who only wish to use him to further their own agendas, John decides to return to Africa and reunite with his ape family. Phillippe and Jane escort him back to his jungle, where he reunites with his ape friend, Figs. Jane does not join him, but Phillippe is hopeful that perhaps they may someday be reunited.

Cast

[edit]- Christopher Lambert as John Clayton/Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, a man orphaned in the jungle who was adopted by a group of apes and became their leader and is the last member of the Greystoke lineage

- Tali McGregor as Infant Tarzan

- Peter Kyriakou as 1-year-old Tarzan

- Danny Potts as 5-year-old Tarzan

- Eric Langlois as 12-year-old Tarzan

- Ralph Richardson as The 6th Earl of Greystoke, John Clayton's grandfather who is the current Earl of Greystoke and confuses John for his son due to grief and his deteriorated memory

- Ian Holm as Capitaine Phillippe d'Arnot, a Belgian explorer who discovered John in the jungle, taught him the way of man, and brought him to England

- James Fox as Lord Charles Esker, a lord who tries to keep the line of Greystoke intact

- Andie MacDowell as Jane Porter, the Earl's ward who becomes romantically involved with John

- Glenn Close as the uncredited voice of Jane Porter. Close later voiced Kala, Tarzan's adoptive ape mother in the Disney animated adaptation.

- Cheryl Campbell as Alice, Lady Clayton of Greystoke, John's biological mother who dies of malaria

- Paul Geoffrey as John "Jack" Clayton, Viscount Clayton, John's biological father who is killed by his adoptive ape father

- Ian Charleson as Jeffson Brown

- Nigel Davenport as Major Jack Downing, a big game hunter enjoys hunting animals for sport only to eventually become prey to tribal hunters.

- Nicholas Farrell as Sir Hugh Belcher

- Richard Griffiths as Captain Billings

- Hilton McRae as Willy

- David Suchet as Buller

- John Wells as Sir Evelyn Blount

- Paul Brooke as The Rev. Stimson

Ape performers

[edit]- Peter Elliott as Silverbeard, the dominant male of the Mangani troop and John's adoptive ape father. Elliott was also the ape movement choreographer.

- Ailsa Berk as Kala, John's adoptive ape mother who took him in after she lost her infant

- John Alexander as White Eyes, an aggressive male in the troop who has a vendetta against John.

- Christopher Beck as Droopy Ears, a childhood friend of John who was unfortunately killed by a panther

- Mak Wilson as Figs, an overweight member of the troop who is a faithful friend and brother figure of John

- Emil Abossolo-Mbo and Deep Roy as additional ape performers

Development

[edit]Robert Towne

[edit]In August 1974 producer Stanley Jaffe announced Warner Bros had bought the rights to the Tarzan character from the Burroughs estate and wanted to make a new Tarzan film. "It won't be a caricature or a popularization", he said. "It will be a serious period action adventure true to the characters and done in terms of contemporary mores." Robert Towne signed to write the script. No director or cast was attached but the producer said "I expect the Tarzan we'll cast won't be a muscle man."[5]

Towne later recalled, "I called up a friend and said, "Let's do it." But he says, "Oh, damn man, that's going to be a problem"—because an associate of his had met resistance trying to put together a Tarzan film. Oh, no, come on—Jane Goodall, Shadow of Man. We could actually do it now as if it really happened. And my friend said "You’re right, screw it, let's do it"."[6]

In September 1975 a report said the film would be made the following year. "It's a very heavy story", said Towne. "Very sensual. Basically it's about Tarzan and his foster mother."[7] The film had a tentative budget of $6 million and a working title of Lord Greystoke.[8]

Towne said working on the script is what made him want to direct. "I suddenly realized that I'd written a bunch of descriptions without much dialogue to go along with it", he said. "I'd reached the age where I realized that I couldn't necessarily just turn that over to a director and say "Don't fuck it up." It's just a bunch of descriptions, and then it became embarrassingly apparent to me that those were what I saw when I wrote them down. There was nobody else who could see them, so I needed to direct... The distance between the page and the stage is so enormous that it is unbelievable how even the brightest people can misread your intent or not see it altogether. Scripts have air in them. Scripts are supposed to leave things up to interpretation, but people can misread things enormously, so sometimes it's just a matter of wanting to put on the screen what you had in mind."[9]

By October 1977 Towne was attached as director as well as writer. Anthea Sylbert was appointed Warners executive in charge of the project.[10]

Towne made his directorial debut on another project he had written, Personal Best. This movie, about female athletes, came out of Towne's interest in human movement, which arose from his research into Greystoke. He intended Personal Best to be a "trial run" for Greystoke. However filming Personal Best proved extremely difficult – Towne had to deal with an actors strike and a budget blow out. He wound up in conflict with producer David Geffen and Warners that led to him selling his interest in Greystoke.[11][12]

"Greystoke may be the kid I love the most, but I was eight months' pregnant with Personal Best, so that's the kid I had to save", said Towne. Part of the $1 million that Towne received for Greystoke was put in escrow to be held against any money he went over budget on Personal Best. Towne later said he was practically broke. "Nobody can believe how mucked up financially you can be by these studio guys. But a cab driver in New York who doesn't get tipped gets more sympathy than any Hollywood writer." Personal Best was a box office flop.[13]

In 2010 Towne said losing Greystoke was "then, is now, and always will be the biggest creative regret of my life."[14]

Hugh Hudson

[edit]A new director became attached to the project – Hugh Hudson whose debut feature Chariots of Fire had been a surprise box office hit. "Towne's script was brilliant", said Hudson. "It was only half finished and overlong but all the jungle stuff was there and it was fascinating. I said yes at once."[3]

Hudson was going to make the film with his Chariots producer, David Puttnam. Makeup artist Rick Baker signed to create the ape makeup.[15]

Puttnam eventually pulled out and went off to produce Local Hero instead. "After looking into it carefully I felt it needed a more experienced producer", he said. "I've never worked with special effects and frankly they terrify me. And on that film you need someone who's done that. I'd have been learning on the job and that could have proved expensive and one of the things I rely on is people's belief that I can deliver good value for money. I had this awful vision of Greystoke going over budget and my whole reputation going down the drain."[16]

Hudson said, "I think he [Puttnam] felt he had lost control because it was a studio picture set up by Semel and Daly and they wanted to deal directly with me, and he had this other film going, The Killing Fields, that he probably wanted to do more. Stanley Canter [who's credited as producer alongside Hudson] had a deal with Warners and the Edgar Rice Burroughs estate, but he wasn’t involved in the making of the film."[2]

Hudson had the script revived by Michael Austin. They spent nine months on it.[2]

Hudson said the film was "about Adam and Eve, the Garden of Eden. It's about the loss of innocence and about the evolutionary urge. This boy is discovered by a Belgian, d'Arnot, and he's taught language. Up to that point he's very contented, but d'Arnot is the snake in the myth. He gives him the word, and from that point you could say he's lost. The question is, does he have to go on to join society, or not? The story asks you to consider how society lives, halfway between the apes and the angels, aspiring to go up yet coming from down there. It's about the battle of nature and nurture, nature and culture – a dilemma, a terrible dichotomy in us all. It's about the freedom of the jungle and the distortions and strictures of society, and how perhaps we can't do without either of them. There's not enough nature in society, and maybe not enough society in nature. The thing is about that sort of balance, which is so tender, so difficult to achieve, yet so essential to all of us. It's about two opposing forces, which shouldn't be opposing at all."[17]

Towne had done tests involving real apes but Hudson felt this was too difficult and decided to use humans in ape costumes.[2]

Production

[edit]Casting

[edit]Hudson wanted to cast unknowns as Tarzan and Jane. "They are complete innocents, and therefore somebody new is more acceptable to the audience than a face you know. They also represent the innocent side of ourselves, and we should be able to identify with them. So Tarzan is what we might be, if we had lived like that: light, lithe, every muscle used, but not rippling like a Charles Atlas."[17]

Hudson tested four people as Tarzan: a Danish ballet dancer, Julian Sands, Viggo Mortensen and Christopher Lambert. Hudson said it came down to Lambert and Mortensen. "I just felt that Christopher was the right person. He had this strange quality – somehow, because he was myopic, when he took his glasses off, he couldn’t really see properly so he would seem to look through you into the distance."[2]

Andie MacDowell made her film debut as Jane. "The camera loves her, and I just felt she was the right person", said Hudson. "Of course it's a risk, but then the whole project is a risk. If I'm a good director I'll get the performance I want out of her."[17]

Preparation

[edit]Hudson used Dr. Earl Hopper, the American author of Social Mobility, as an adviser on the film's psychological and social plausibility. He also used Professor Roger Fouts of the Central Washington University, a primatologist who has successfully instructed chimpanzees in sign language for the deaf.[17]

"Tarzan is everyman, and he is also everyman's idealized projection of himself", said Hudson. "We all aspire to be how he is, morally and physically. We'd all love to have that body, be wild, swing in the trees, and get the ideal woman, who is Jane. And all that, all that meaning, is dressed up in a terrific 'Boys Own' story, a marvelously exciting adventure yarn."[17] In preparation for the movie, Christopher Lambert trained with real apes and said " I wasn't afraid of them, but you must show them respect."

Shooting

[edit]-

Floors Castle in Kelso

-

Hatfield House in Hertfordshire

-

Ekom Waterfall in Korup National Park

Filming started in November 1982.[18]

The film was shot in Korup National Park in western Cameroon and in Scotland. Several great houses in the UK were used for the Greystoke family seat:[19]

- Floors Castle near Kelso in Roxburghshire, Scotland, is used for the exterior and ballroom scenes,

- Hatfield House in Hertfordshire (entrance hall, grand staircase),

- Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire.

Greystoke was the first Hollywood film to be shot in the Super Techniscope format.

Post-production

[edit]The dialogue of Andie MacDowell, who played Jane, was dubbed in post-production by Glenn Close. According to Hugh Hudson, this was due to MacDowell's southern US accent, which he did not want for the film, and that she was not (at the time) a trained actor.[2] The young Jane featured at the beginning of the film is portrayed as American, which is consistent with Burroughs' story.

Ralph Richardson, who played The 6th Earl of Greystoke, died shortly after filming ended, and he received a posthumous Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. The film was dedicated to his memory.

Warner Bros. cut out 25 minutes from the jungle footage of Tarzan growing up. "I was sorry to lose those scenes", said Hudson. "But you can't have everything."[3]

John Corigliano was considered to compose the film score, but he was unable to commit to the job due to scheduling conflicts.[20] Vangelis was also considered, but according to Hudson, he got "writer's block", so the production hired John Scott, "and he did a very good job in a very short space of time", said the director.[2]

When the film finished, Hudson said that the result was "70%" of the film that he wanted to make.[3]

Relationship with other Tarzan stories

[edit]In a departure from most previous Tarzan films, Greystoke returned to Burroughs' original novel for many elements of its plot. It also utilized a number of corrective ideas first put forth by science fiction author Philip José Farmer in his mock-biography Tarzan Alive,[citation needed] most notably Farmer's explanation of how the speech-deprived ape-man was later able to acquire language by showing Tarzan to be a natural mimic. According to Burroughs' original concept, the apes who raised Tarzan actually had a rudimentary vocal language, and this is portrayed in the film.

Greystoke rejected the common film portrayal of Tarzan as a simpleton that was established by Johnny Weissmuller's 1930s renditions, reasserting Burroughs' characterisation of an articulate and intelligent human being, not unlike the so-called "new look" films that Sy Weintraub produced in the 1960s.[original research?] The second half of the film departs radically from Burroughs' original story. Tarzan is discovered and brought to Scotland, where he fails to adapt to civilization. His return to the wild (having already succeeded his grandfather as Lord Greystoke) is portrayed as a matter of necessity rather than choice, and he is separated, apparently, forever from Jane, who "could not have survived" in his world. In his book Harlan Ellison's Watching, Harlan Ellison explains that the film's promotion as "the definitive version" of the Tarzan legend is misleading. He details production and scripting failures which in his opinion contribute to the film's inaccuracy.[further explanation needed][21]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film grossed $45.9 million upon its release, making it the 15th most popular film at the box office in 1984.[22]

Critical reception

[edit]Colin Greenland reviewed Greystoke for Imagine magazine, and stated that "If there's a better film this year than Greystoke, I shall be astonished."[23]

Film review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported an approval rating of 73%, based on 15 reviews, with a rating average of 5.96/10.[24]

Accolades

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Greystoke – The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 8 March 1984. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Galloway, Stephen (July 2016). "The Secrets Behind That Other Tarzan Movie – The One That Earned a Dog a Screenwriting Oscar Nomination". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Mann, Roderick (25 March 1984). "MOVIES: SWINGING BACK TO THE ORIGINAL 'TARZAN'". Los Angeles Times. p. l19.

- ^ "The Charlotte News, 29 March 1984". The Charlotte News. 29 March 1984. p. 41. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (4 August 1974). "News of the Screen: A New Tarzan From Old Novel Major Film Due on War in Spain Davidson Taps I. B. Singer Novel Mishima 'Sailor' To Be Made in West". The New York Times. p. 43.

- ^ "Robert Towne". Creative Screenwriting.

- ^ Meyers, Robert (1 September 1975). "Edgar Rice Burroughs' Days of Vines and Poses: Edgar Rice Burroughs' Days of Vines and Poses". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Riley, John (7 September 1975). "Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Fruits of Pulp: Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Fruits of Pulp". Los Angeles Times. p. s1.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (14 March 2006). "Interview with Robert Towne". The A.V. Club.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (5 October 1977). "FILM CLIPS: Begelman Inquiry at Columbia". Los Angeles Times. p. h8.

- ^ Pollock, Dale (29 January 1982). "Towne: Toughing It Out to the Finish Line". Los Angeles Times. p. g1.

- ^ Pollock, Dale (15 April 1982). "$155-Million Lawsuit Over 'Best'". Los Angeles Times. p. i1.

- ^ Harmetz, Jean (15 April 1982). "Writer-Director Sues for $110 Million". The New York Times. p. C.27.

- ^ "Robert Town Returns". Today. 2010.

- ^ Pollock, Dale (31 March 1982). "The 100 Dramas of Oscar Night". Los Angeles Times. p. f1.

- ^ Mann, Roderick (20 February 1983). "Movies: Producing Is All Puttnam Wants To Do". Los Angeles Times. p. s18.

- ^ a b c d e Nightingale, Benedict (6 March 1983). "After 'Chariots of Fire', He Explores The Legend of 'Tarzan'". The New York Times. p. A.17.

- ^ Steve Pond (11 November 1982). "Dateline Hollywood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Film locations for Greystoke, the Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984)". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ "War Is Hell: John Corigliano and the Battle Over REVOLUTION". Words of Note. 19 March 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan, Harlan Ellison's Watching. Underwood-Miller, 1989.

- ^ "1984 Yearly Box Office Results – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Greenland, Colin (July 1984). "Fantasy Media". Imagine (review) (16). TSR Hobbies (UK), Ltd.: 49.

- ^ "Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984) – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "The 57th Academy Awards (1985) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Greystoke: La légende de Tarzan, seigneur des singes (1984) Prix & Festivals". Mubi. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1985". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). British Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "The 1985 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (3 January 1985). "'Stranger Than Paradise' wins award". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "'Passage' Wins Two Big Awards". Observer-Reporter. 20 December 1984. Retrieved 28 December 2017 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes at IMDb

- Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes at AllMovie

- Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes at the TCM Movie Database

- Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes at Rotten Tomatoes

- Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes at Box Office Mojo

- 1984 films

- 1980s adventure drama films

- 1980s fantasy adventure films

- American adventure drama films

- American fantasy adventure films

- British adventure drama films

- British fantasy adventure films

- Films shot at EMI-Elstree Studios

- Films directed by Hugh Hudson

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films set in 1885

- Films set in 1886

- Films set in 1887

- Films set in the 1890s

- Films set in 1891

- Films set in 1898

- Films set in the 1900s

- Films set in 1906

- Films set in Africa

- Films set in Scotland

- Films shot in Cameroon

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Films shot in Oxfordshire

- Films shot in the Scottish Borders

- Films with screenplays by Robert Towne

- Films scored by John Scott (composer)

- Tarzan films

- Warner Bros. films

- 1984 drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s British films

- English-language fantasy adventure films

- English-language adventure drama films